AI in a historical landmark: DFKI Osnabrück takes off in a railway roundhouse

Interview with Prof. Dr. Joachim Hertzberg and Prof. Dr. Oliver Thomas

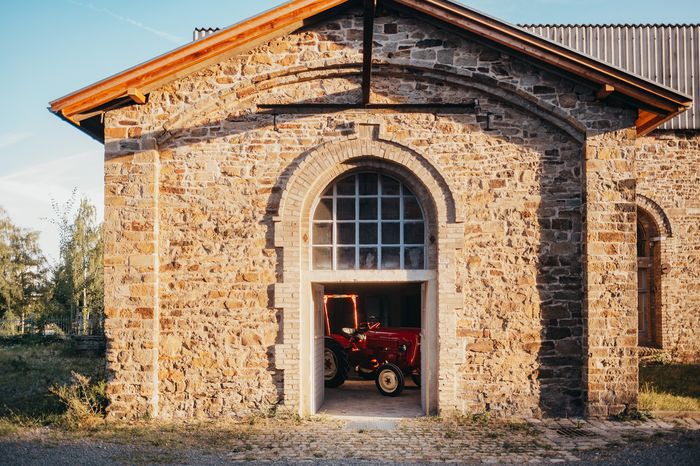

The DFKI Niedersachsen is the newest DFKI location. A few weeks ago, researchers from the two Osnabrück research departments moved into a railway roundhouse built in 1914. Prof. Joachim Hertzberg and Prof. Oliver Thomas give us a tour of the new 2,800 m² workspace and explain, almost a year after the site’s official inauguration, why the move is a milestone, what topics they are currently working on, and why AI works so well in the regional context.

This interview was originally written in German and translated into English.

Recently you started working in a restored historical landmark. The DFKI has rented eleven sections, known as locomotive sheds, in the Coppenrath INNOVATION CENTRE (CIC), which is currently under development. How did that come about?

Joachim Hertzberg: The Coppenrath Foundation had the opportunity to acquire the formerly dilapidated building in Osnabrück's railroad district and asked us, quite early on, what we would do with it and whether we would be interested in developing it into something. At that time, we both said quite spontaneously: Wow, cool building, great idea, that would suit us very well.

Oliver Thomas: It was also related to our growth. At first, our university groups were spread out in different buildings throughout the city. These rooms were practically empty at the beginning, but after a year they were not enough anymore. We realized that the DFKI Niedersachsen was not a matter of five to ten people, but that it was getting bigger. Now we are here together in one place with around 90 researchers plus student assistants and with a clear tendency to grow even further.

What kind of people work there?

Joachim Hertzberg: In my department, "Plan-based robot control," we mainly have computer scientists, cognitive scientists and physicists, but also people from other disciplines.

Oliver Thomas: My team is closely related to business informatics, business administration and industrial engineering. Basically, we can map an entire value chain through our employees. There are people with in-depth and core knowledge of AI technologies. They can translate the technologies into concepts and prototypes and also implement them on enterprise systems. Some companies like to get technical guidance or advice on applications they already have in the data analytics field that can be enriched with AI. Others don't have a plan yet and are wondering what their AI agenda might actually look like in conjunction with a digital strategy. At each point, we have experts.

The move happened a few weeks ago, what happens next?

Joachim Hertzberg: We will now finish getting settled in. At the moment, for example, we're still missing seating and furniture for meeting areas. Some of these have to be specially manufactured so that we can make good use of the free space and the potential of the building. This is a rather time-consuming process that will probably continue until the end of this year. Of course, we are already working in our new rooms, but only then will we have moved in completely. There will also be an open day, of course.

Why is a high-tech institute like the German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI) located in Osnabrück, a city many people don't know?

Joachim Hertzberg: From an academic point of view, AI has been deeply rooted in Osnabrück for a long while. At the University of Osnabrück, but also at the University of Applied Sciences, AI has existed as a teaching and research topic for a long time. The Institute for Semantic Information Processing at the university was founded in 2001. I came to the university in 2004 for my professorship in "Knowledge-Based Systems". At that time, no one noticed how strongly AI was located here, because no one outside the university was interested in it. When the DFKI was founded in Lower Saxony, it was very clear to us that if you wanted to establish an AI location somewhere in Lower Saxony, Osnabrück would be a very obvious place to do so, because there is a scientific and technical tradition here.

Many people also don't know about the strong medium-sized economy here in the region. Osnabrück is a key player in agricultural engineering, agrifood, food processing and logistics, even on a national scale. It's not enough to just install great beacons of AI research in Berlin, Munich, or Dresden. Emsland can't get anything out of that. We have to take the cool new ideas to the people who need them, especially to the companies that need them. We are in a place that has had an industrial structure for over 110 years, we are just doing something in a completely "renovated" way — with AI. It's about completely different processes, new emergent structures, different ways of getting products, but also a different kind of basic research.

We are in a place that has had an industrial structure for over 110 years, we are just doing something in a completely "renovated" way — with AI.

Oliver Thomas: The business information scientists in my field want to know which stumbling blocks companies have. And we find this target group here in Osnabrück, a top SME (small and medium-sized enterprise) region in Germany. In Osnabrück, there aren’t only craft businesses with 25 people, but also large medium-sized companies with revenues between 100 million and 2 billion euros, some of which are still owner-managed. Here we can optimally carry out the transfer. This also applies to spin-off companies in sectors that are very close to us. We actively encourage entrepreneurship and are constantly expanding it. In Joachim's department a new company is currently being set up, Nature Robots GmbH, which is developing robots for a new type of vegetable cultivation. Strategion GmbH, which emerged from my team 12 years ago, advises companies on the implementation of digital technologies. Didactic Innovations GmbH is also one of my spin-off companies. It provides support for didactic transformation.

Joachim Hertzberg: By the way, these regional medium-sized companies that we often work with in projects also have a long-term view and they don't have to look at short-term optimization. There are clear lines in terms of who to approach. You often talk directly to the owner or the head of predevelopment and find out very clearly where they want to go, what they want to do, or don't want to do. I find it positive to talk to companies such as these, and this is a strength that we can definitely exploit from the business side.

The CIC is interwoven with the region simply by its historic building. What are examples of regional cooperation in your research departments?

Oliver Thomas: For us, one important task right now is to put together the right service packages for companies and to explain how we can support them in their AI transformation. For this purpose, we are active in several initiatives that also address the SME sector in and around Osnabrück. In the Green-AI Hub SME, we carry out AI pilot projects in companies where, with the help of AI, resources can be used more efficiently in order to protect the environment. We are doing this on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment.

With the European Digital Innovation Hub CITAH, we provide services that facilitate an initial, low-threshold contact with AI for companies in the region, for example via networking events or test-before-invest prototype applications. The companies and hidden champions here are positioned globally, they know their products well, and they know all about customs and internationalization. A practical and demonstrably useful deployment of AI, however, is hardly taking place at present. A concrete understanding of what AI can mean for their value creation is still missing. The potential for collaboration is huge. In some way, our activities also fit our new location quite well. And that's where things come full circle. AI doesn’t exactly occur in isolation, but in combination with other technologies. Just like with Coppenrath's frozen cake back in the day, when the longevity of their components and logistics shaped their business success, in the CIC we want to tap into technology bundles with AI that break new ground for companies' business models today.

AI doesn’t exactly occur in isolation, but in combination with other technologies. Just like with Coppenrath's frozen cake back in the day, when the longevity of their components and logistics shaped their business success, in the CIC we want to tap into technology bundles with AI that break new ground for companies' business models today.

We are also cooperating with the Museum Industriekultur (MIK) Osnabrück. In our showroom, a former coal washing plant, we use demonstrators to make our research more accessible to the general public and show that AI applications make sense and offer value. We started with a red Porsche Junior 108 tractor, on which we demonstrated the possibilities of augmented reality and AI for repair tasks. Currently, the focus is on logistics. Visitors learn how a package gets to the customer. In the past, only goods were transported, but today data is also transported with the goods. This data transport is not only organized, but also optimized with AI processes. To explain this change, an employee of the Osnabrück-based logistics service provider Hellmann Worldwide Logistics was also included in the current MIK exhibition. He reports on what the processes used to look in the past.

© DFKI, Tobias Schwertmann

© DFKI, Tobias Schwertmann © DFKI, Tobias Schwertmann

© DFKI, Tobias SchwertmannProf. Hertzberg, how does your research department cooperate in the region?

Joachim Hertzberg: With the computer science topic of "Plan-based robot control" (PBR), I am located more at the core of AI research. Because we clearly wanted to do transfer research from the very beginning, I was also always of the opinion that, as a computer scientist, you have to understand something about the area into which you want to transfer. That's why we as PBR decided to focus on agrifood and agricultural technology and to get involved in this sector. This has worked very well here in the so-called Agrotech Valley. We work together with partners in various funding projects. Basically, there are two lines of application for AI. The industry has long been working on optimizing machine control, for example for driver assistance. The big long-term challenge is not only to improve existing machines, but also to think about other processes, especially in crop production, which in turn require the development of other machines, ultimately robots.

Do you have specific venues for this as well? That doesn't all happen in the CIC, does it?

Joachim Hertzberg: Sure, crop production is something that has to happen in the field. We are active on several farms and areas around Osnabrück. At Gut Arenshorst, the DFKI has various test areas on a former golf course. We are currently testing autonomous robots there for a new type of vegetable cultivation and the monitoring of rapeseed in a market garden created by our master gardener. There is also a test field with a carriage that moves along a rail system and is equipped with sensors, which we use to test AI algorithms for the environmental perception of autonomous agricultural machinery under conditions such as rain, fog and dust. Safety is an important topic right now. How can the functional safety of machines that have AI components be certified or at least validated in the first place? That's still completely unclear, but it's a crucial issue for their legal use. The new agrifoodTEF initiative is also about creating the technical and spatial conditions for this and developing appropriate methodologies. Together with Osnabrück University of Applied Sciences and Agrotech Valley e.V., we will establish the German node for AI-based agricultural technology in arable farming here in Osnabrück.

© DFKI, Annemarie Popp

© DFKI, Annemarie Popp © DFKI, Annemarie Popp

© DFKI, Annemarie Popp © DFKI, Annemarie Popp

© DFKI, Annemarie PoppContact

Jennifer Oberhofer

Communications & Media Niedersachsen

jennifer.oberhofer@dfki.de

+49 541 386050 7088